Public Transit Isn’t a Public Good Until We Fund It Like One

Transit, as a government enterprise, too often is treated like a business. But as life post-pandemic changes, now is the time to reassess transit funding.

Transit is an essential component for the functioning of cities. Regardless of whether someone is a frequent or non-transit user, everyone benefits. More than ever, public transportation is essential for the prosperity and recovery of urban areas. But transit agencies across the country face a fiscal crisis. Sustained pandemic-related aid, if not more, is needed to allow transit systems to operate sufficiently for the millions they serve.

In a recent Bloomberg article, Jim Aloisi, a professor in transportation policy and planning at MIT described the issue:

A lot of agencies are going to hit the fiscal cliff either next year or the year after, and it’s not going to be pretty. The problem is structural and it has to do with how agencies have relied too heavily on fare revenue.

Instead of focusing on farebox revenue, transit systems need to be treated like the public good they are and funded appropriately. Below discusses the current fiscal crisis transit systems face, farebox recovery ratios, ridership recovery, and why transit is crucial for cities.

Transit Systems Around the Country Face a Fiscal Crisis

Transit systems throughout the country are currently facing a fiscal crisis causing serious problems for commuters and transit authorities. Due to a lack of funding, many transit networks are struggling to provide the level of service that riders have expect.

Back of the Budget recently covered the MTA’s fiscal issues in the context of New York State’s 2024 budget and the Eno Center for Transportation covered the magnitude of their fiscal cliff last year. But the MTA, although the largest transit agency in the country, is not alone.

Here are some other large regional transit systems under pressure:

CTA, Metra and Pace; Chicago Metro Area: Warning of a looming 'fiscal cliff,' the RTA seeks more tax aid Crain’s Chicago Business

WMATA; Washington, DC Metro Area: Metro ridership rises, but not enough to alter financial projections Washington Post

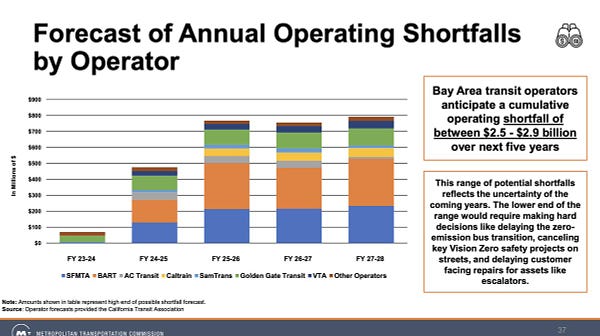

BART, Caltrain, AC Transit and San Francisco’s Muni; Bay Area California: Will Southern California rescue Bay Area transit? Hearing sets stage for multi-billion dollar budget battle Mercury News

Transit systems, irrespective of their size, are grappling with a crisis that stems from a fundamental issue: overreliance on farebox revenue. This has created a structural problem affecting their overall operating model. Revenue from fares has long been inadequate to cover operational expenses. Agencies have continually struggled to maintain and improve services, and fund capital improvements, while also ensuring they remain financially viable.

Transit Isn’t a Good Business, Let’s Stop Treating it Like One

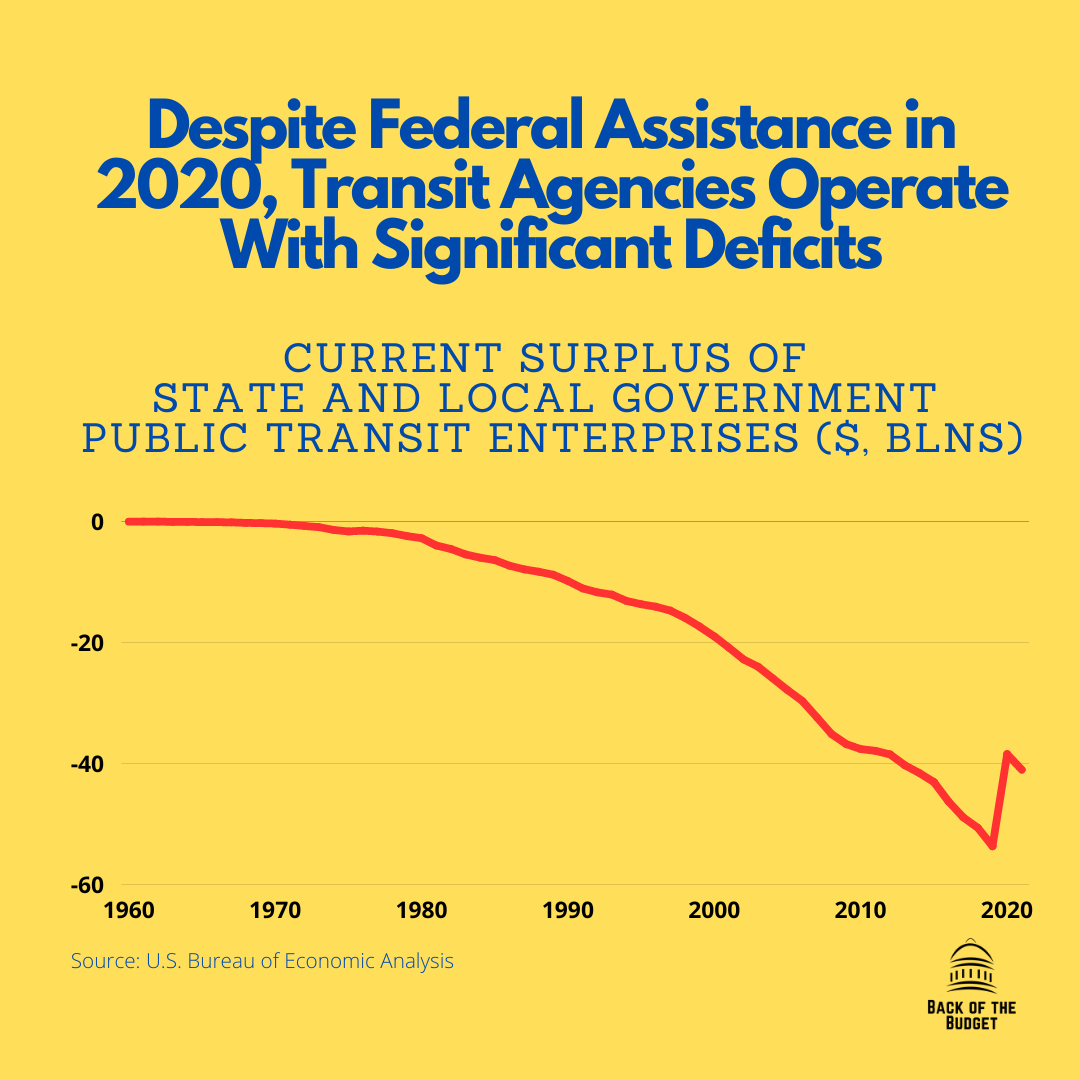

Government enterprises are public organizations that function akin to commercial businesses. They should, by definition, generate a significant portion of their operational revenue from the sale of goods and services. In 1960, the current surplus, or “current operating revenue and subsidies received by government enterprises from other levels of government less the current expenses,” for public transit was –$0.1 billion, but by 2019 the current surplus was -$55 billion.

Transit isn’t a good business, and we should stop viewing it like one — but it is essential. While many view transit agencies as a government enterprise, reliance on fare revenue has been declining on average.

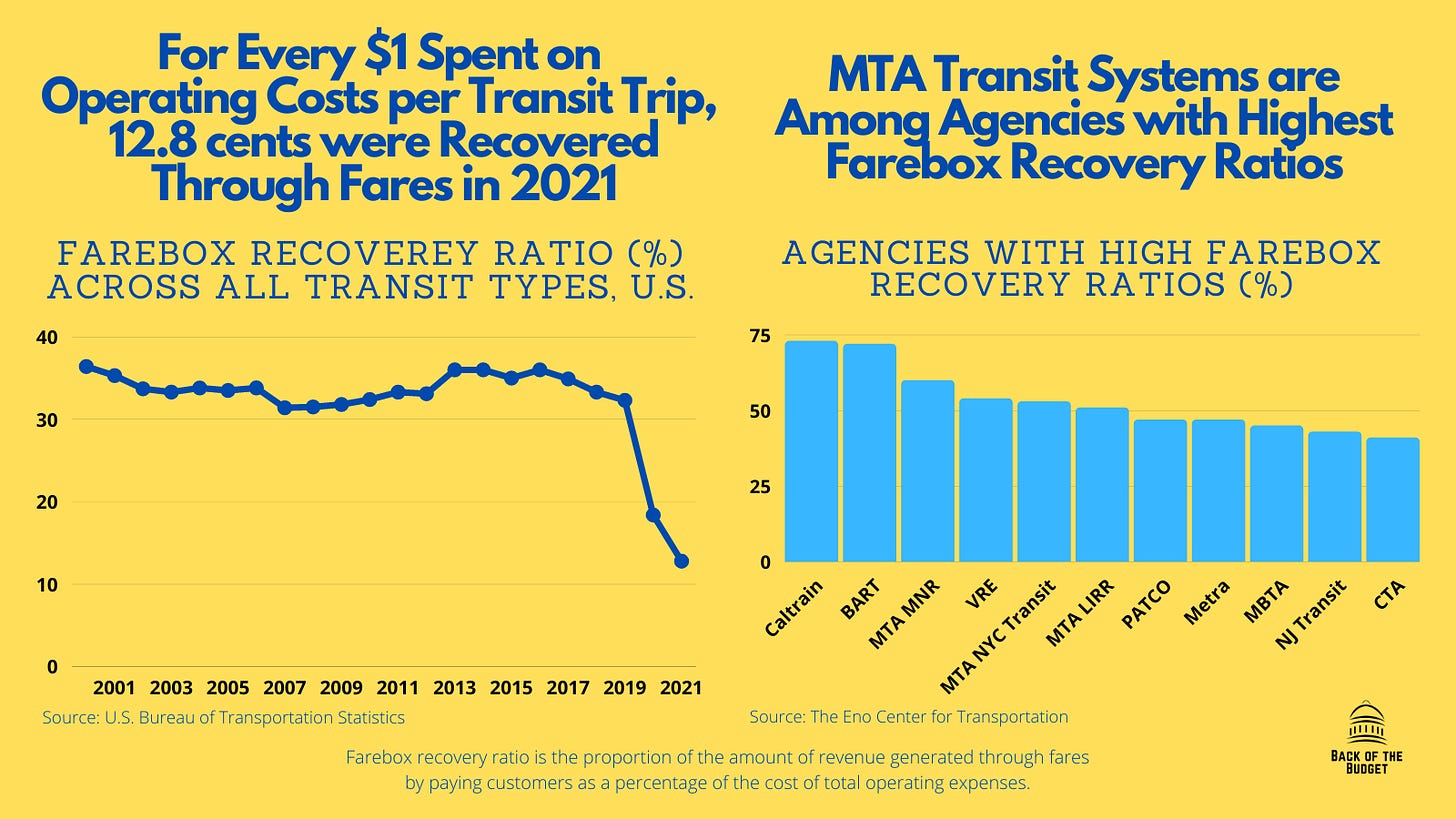

From 2000 – 2019, the average farebox recovery ratio, or the percent of a trip’s operating costs recovered through passenger fares, declined from 36% to 32%. Federal aid filled some of the lost revenue from riders the past few years, but significantly less ridership resulted in the average farebox recovery ratio reaching an all-time low of 12.8% in 2021. With slow ridership recovery that may plateau at a level well below what we saw in 2019, all levels of government may need to provide additional support to transit agencies.

Elected officials should look to reduce transit’s dependence on farebox revenue which has resulted in systems struggling to remain financially sustainable. Tax subsidies can provide a more stable and predictable source of funding, allowing for improved long-range planning and sustained investments in infrastructure, maintenance, and innovation.

Transit Ridership Might Recover, But Will Likely Take Years

New York City’s transit system, in particular its subway, has a flatlining ridership recovery. There was a visible increase in September weekday recovery coinciding with the start of the school year. However, recovery has averaged 75% since then. A 25% reduction in weekday ridership will have a substantial effect on operations and revenues for agencies across the U.S.

In January 2023 report, S&P Global Ratings analysts estimated:

The recovery in public mass transit will continue to materially lag all other U.S. transportation infrastructure asset classes due to a slow or partial return to office commuting patterns. Our revised baseline activity estimate for transit shows a faster recovery (80% by 2025 instead of 75%; and 85% by 2026) compared with our July 2022 estimates.

They also note that considering U.S. transit ridership was already in decline before the pandemic, recovery will take years and depend on slowly evolving demographic trends.

If you look at current transit recovery trends since September 2022, we could see a full recovery by 2025 (Scenario 1) — but that is unlikely. Considering telework opportunities will likely result in 1 to 3 days of less transit ridership per week for many, ridership recovery will slow. Potentially with 80% recovery by 2026 and 85% by 2028 (Scenario 2). In areas like New York City and San Francisco, where the “return to office” movement has been slower than other metro regions, recovery may take longer.

If transit ridership is slow to recover, agencies will need revenue other than the farebox. Without sufficient funding, transit systems will be forced to reduce services or increase fares, which could further negatively impact ridership recovery — a doom loop for these agencies.

To maintain a healthy transit system that serves the public, governments will need to step in with additional tax subsidies or other revenues to support operations. This will be critical to maintaining and improving services, essential for the functioning of cities.

Transit is a Shared Experience and Celebration of the City We Cannot Lose

In April 1970, Stephen Sondheim’s Company opened on Broadway. “Another Hundred People,” sung by a newcomer to New York City, marvels at the city’s subway. The city is portrayed as a "musical" that never stops, with a never-ending flow of individuals coming and going like notes in a song. It is also a representation of the frantic pace of urban life, and how transit enables people to move with ease.

Transit is an important reminder of our shared humanity and the ways in which we are all connected. And while we may not always interact with one another directly, the simple act of being near so many other people can be comforting and affirming, reminding us that we are part of something larger than ourselves. In this way, transit systems are not just a means of getting from point A to point B, but a vital part of the social fabric of our cities and communities.

Any opinions expressed herein are those of the author and the author alone.